|

|

(Vintage photos courtesy of The Baltimore Family) (Vintage photos courtesy of The Baltimore Family)

Jesse Robert Baltimore (1890-1959)1

|

Jesse Robert Baltimore was the prototype of the Modern Homes customer, a man with building skills who wanted the best possible home for his family. But the history of his Sears Roebuck "Fullerton" exemplifies a larger pattern; the evolution of the Palisades as a streetcar suburb and development of the kit house phenomenon through the experience of an individual family.

Mr. Baltimore was born near Charlottesville, Virginia in 1890 and came to Washington in 1915. For his first seven years in the city, Mr. Baltimore led the nomadic renter's existence of skilled blue-collar tradesmen of the time. After renting accommodations at 1004 C Street SW while working as a mechanic, he moved to 427 G Street NW and began working as a plumber by 1917. In 1920 Mr. Baltimore, who served in the Army Tank Corps during World War I, worked as a mechanic and lived at 29 N Street SE.

|

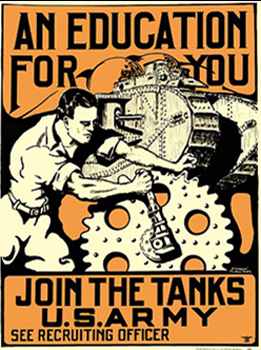

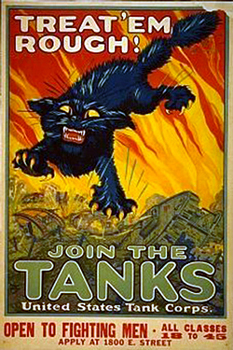

Tanks, World War I's high-tech counter to the machine gun, required the mechanical skills of men like Jesse Baltimore.

|

In 1921, while working as a plumber for the W.H. Mooney Company of 726 Eleventh Street NW, Mr. Baltimore resided at 737 Seventh Street SE. In 1922 he moved to 509 H Street NW. Around that time, he married Mary Gladys Pilkerton, who had come to Washington to work in a downtown department store.I

The site of the Jesse Baltimore House at 5136 Sherier Place NW was originally occupied by a small one-story frame house which predated the formalities of the building permit system. It is unclear whether Mr. Baltimore modified this original house or razed and rebuilt it. However, during the first two years after they moved to Sherier Place in 1923, the Baltimores lived in a small frame building at the rear of the lot.

On September 24, 1924, Mr. Baltimore obtained a permit to build a two story dwelling designed by architect L.T. Burn. However, District inspectors visited the site week after week and reported work “not started”. Then, on July 7, 1925, Mr. Baltimore obtained another building permit, this time for a house whose architect was listed as “Sears Roebuck”

|

Although Jesse Baltimore completed training for the tank corps, the war ended before he could be sent overseas.

|

The model Mr. Baltimore selected was the “Fullerton”, an “Honor-Bilt” house (Sears’ highest quality) offering 1,932 square feet of living space in a six-room, two-story, American Foursquare design. Foursquare-style houses had achieved peak popularity in the first two decades of the twentieth century, but by the early 1920s were losing ground to bungalow styles. However, by then the Foursquare style had become an American classic. Robert Schweitzer and Michael Davis could have been describing Mr. Baltimore’s house when they wrote:

As... a form seen from coast to coast, from plain to fancy, [the Foursquare] really could--and perhaps should--be called 'National,' the true nationwide house…

Sears tellingly advertised the Fullerton as “adapt[ing] itself equally well to city lots or country estates”, making it an especially appropriate match to the village-within-the-city character of the Palisades.

The Fullerton is one of Sears’ larger foursquare designs with more front windows and larger rooms than its more spartan cousins. Its front door gave entry to a full-width living room with fireplace, which opened through a cased entryway to a dining room, flanked by an eat-in kitchen. The second story had three bedrooms and a single bath, which was not a given in the 1920s. One unusual feature of the Fullerton is that there is no backdoor. There is instead, a side door which opens onto a staircase landing between the basement and kitchen.

The Fullerton features narrow lap wooden siding made of cypress, “the wood eternal”, which was a hallmark of 1920s Sears houses. It has a hipped roof, overhanging

|

Mr. Baltimore's Fullerton Foursquare differed stylistically from such Sears bungalow models as the Vallonia (above left) and Westley (above right).

|

|

eaves and a full-width front porch whose hipped roof is supported by stubby wooden pillars with scalloped ornamental depressions. These wooden pillars sit atop masonry columns that rise from ground level. Other Fullerton signature features include the center chimney, a wood-shingled dormer with a small, multi-pane window, and triptiche living room windows whose center sash is roughly fifty percent wider than the windows which flank it.

While no reliable statistics exist regarding the number of houses of each model Sears sold, the number of years each model was included in the catalog is an index of its popularity. Five Sears Roebuck Modern Homes catalogs featured the Fullerton between 1925 and 1933. Although numerous models were featured for only one or two years, the Fullerton’s five year run does not compare to those of such common Sears models as the Vallonia bungalow (twelve years) or the Whitehall Foursquare (nine years). Sears advertisements in The Washington Post illustrated select designs such as The Langston and The Puritan. None of the ads show the Fullerton.

Construction on 5136 proceeded swiftly, with Jesse Baltimore and his brother George Lewis Baltimore completing the house by October 1925. This was in keeping with the ninety-day time frame Sears advertised for constructing its "already-cut and fitted" homes.Mr. Baltimore’s son recalls that his father and uncle completed most of the construction themselves, but contracted out the building of the front stoop and porch pillar piers. Although Sears' plans included provisions for masonry, the company did not supply it with its house kits. This left the choice of style and materials to the buyer. The local mason hired by Jesse Baltimore built the porch piers and stone steps from rough-finished, stone-like concrete blocks topped with granite slabs. Almost 80 years later, they appear to be in excellent shape. The chimney is built of brick.

|

In the Modern Homes Catalog floor plan, the Fullerton's bathroom is illuminated by a single window in the upper story at the rear of the house. In the Baltimore House, this window has been relocated to the rear quadrant of the south side. Perhaps Mr. Baltimore altered the plan to accommodate a preferred arrangement of the bathroom fixtures. Such adaptations were encouraged by Sears, which advertised a “Complete Architectural Service” to provide “the best advice and technical help…to help you build your home as you want it.”

Jesse Baltimore built the Fullerton as a home for his family, which by 1930 included his wife Mary Gladys, their son Jesse Robert, Jr., and Mr. Baltimore’s mother Martha. Eventually the family grew to include two younger sons, George and John. John Baltimore remembers a Palisades boyhood of games on the Recreation Center playing fields, swimming in the C&O Canal, and hitching rides on the trolley to Glen Echo Park. But the house saw tragedy, too, when young George Baltimore was laid out in the living room shortly after striking his head in a tree-climbing accident.

For more than 30 years after building his home, Jesse Baltimore worked in the plumbing trade, which he passed on to his sons Jesse and John. In 1930, he was a plumber at a private school, while in 1940, he was employed by McCarthy and Son Plumbers.

|

|

|

ABOVE LEFT: A scalloped pillar, overhung eaves, and narrow clapboards help mark the Baltimore House as "a Sears".

ABOVE: The Baltimore brothers on the stoop with the canal keeper's son, circa 1942.

LEFT: Jesse Baltimore and a neighbor enjoy a depression-era Palisades Saturday afternoon.

Until shortly before World War II, Mr. Baltimore did not own a car. His son recalls that he commuted to job sites all over the city by carrying his plumbing tools and lunchbox out to Trolley Stop 15, which was almost immediately behind the house. Many of the other men in the neighborhood also worked in the building trades and carried their tools to work on the streetcar.

In 1936, the National Park Service acquired the lot next to the Baltimore House while developing the Palisades Recreation Center across the trolley tracks to the rear of the house. Later a driveway was built to the Rec Center between the house and its northern neighbor.

|

In 1958, Mr. Baltimore and his wife decided to retire to the Chesapeake Bay shore and advertised their house in the Washington Post for $18,500. According to the Baltimores, a family was in the final stages of buying the house when the National Park Service announced that it intended to acquire the property.

For the next 13 years, the Park Service rented the house to a succession of tenants, a practice which continued after the Park Service transferred jurisdiction over the house to the DC Department of Parks and Recreation in 1971. For a time in the 1970s and 1980s, the house was rented to a group home operator. Since the early 1990s, it has been unoccupied despite a wide variety of proposals for new uses from the community.

|

Kit houses, especially those manufactured by Sears Roebuck, played an important role in the development of the Palisades. Because working families in the 1920s and 1930s often could not afford a house and a car, the economies of constructing a kit house near a streetcar line made ownership of a suburban-style detached home a possibility. Houses like the Jesse Baltimore House were an important avenue for working and middle class families to become homeowners in the District of Columbia. Jesse Robert Baltimore was the prototype of the Modern Homes customer, a man with building skills who wanted the best possible home for his family.

Regretably, the Jesse Baltimore House offers a unique display of such intact original Sears details as the narrow-width frame siding, the shingled third floor dormer with three vertical dividers, the original sashes and window pattern, the porch railing and millwork, the center chimney, as well as the hipped upper gable, and porch roofs. In the Palisades, a check of permit addresses and a detailed windshield survey of the neighborhood discloses that more than two-thirds of the identified Sears houses have vanished entirely or been significantly altered, many to the point of being unrecognizable as Sears designs.

The Jesse Baltimore House is the only original and intact Fullerton in the Palisades. The Fullerton model was never common in Washington, DC, and the Jesse Baltimore House is also the most intact and authentic example among the five Fullertons identified in the city.

For these reasons, the Jesse Baltimore House should be entered in the the DC Inventory of Historic Sites.F

|

The Sears Catalog could fill a finished Fullerton with everything from wallcoverings and end tables to lampshades and hand towels.

CLICK HERE FOR "STREETCARS, SEARS HOUSES, AND THE PALISADES"

CLICK HERE TO VISIT "VICTORIAN SECRETS OF WASHINGTON, DC"

CLICK HERE TO RETURN TO "SAVE THE JESSE BALTIMORE HOUSE"

|

|

|