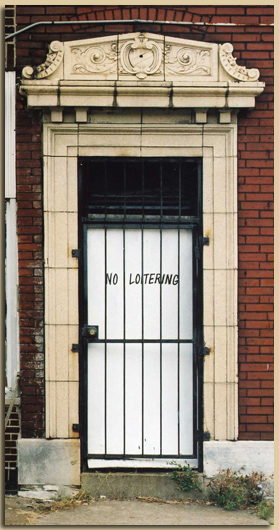

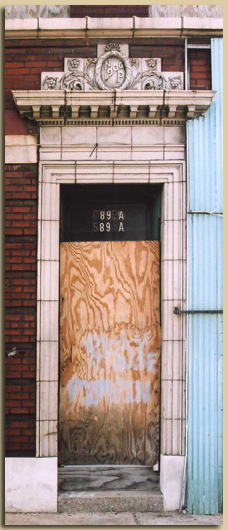

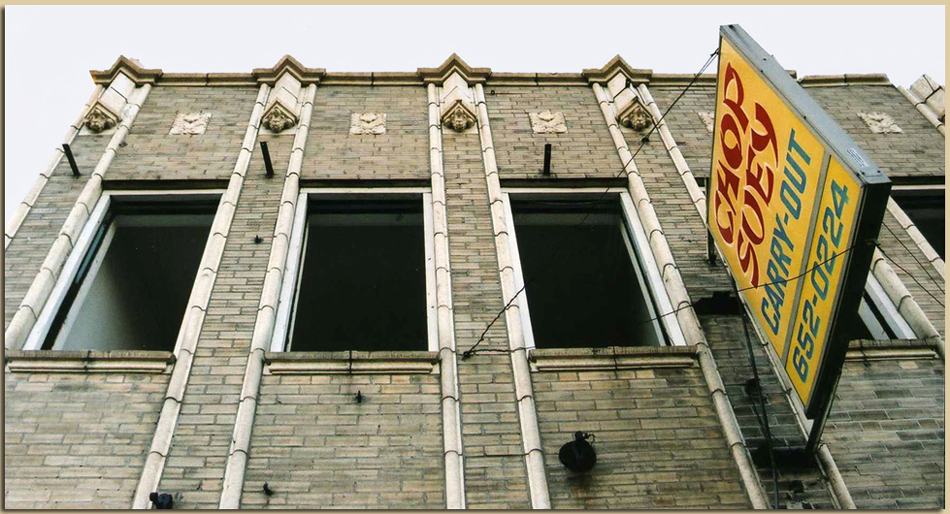

BOTTOM: During the 1920s, terra cotta broke out of its classical motifs and became popular as glazed polychrome tile. Many factories of the era used terra cotta tile facades to suggest that they were bright, clean, and modern, with no connection to the dim, dismal, Dickensian brick Victorian workhouse. It is particularly fitting that the old Mutual Cleaning Company plant on Martin Luther King Avenue is faced with this material and particularly ironic that it now appears to need a serious cleaning itself.

Terra cotta has two natural enemies. One, ironically, is water. When decades in the elements craze a glazed terra cotta surface, minute cracks allow moisture to soak into the porous layer of fired clay underneath. When the water freezes, its expansion "spalls", or fractures the surface, leaving a pockmark. In an extreme case, a spalled ornament can look like it was blasted with shotgun pellets. Also, most ornamental terra cotta is hung on metal mesh or support bolts. When sealing fails and water rusts these supports, elements can fall of their own weight.

The other enemy is the architectural salvage market. Like cemetery headstones, stained glass windows, or iron gates, vintage terra cotta ornaments are known to disappear long before a building is faced with demolition. While it is not known how it happened, the Mutual Cleaning building is now missing most of its cornice ornaments.