Jesse Baltimore's Sears Roebuck "Fullerton"

5136 Sherier Place NW

|

Street Cars, Sears Houses, And The Palisades

The Palisades neighborhood takes its name from the cliffs that overlook the C&O Canal and Potomac River just northwest of Georgetown.

Long a rural enclave within Washington, DC's limits, the Palisades began as a pathway between the wharves and warehouses of Georgetown, the farmlands of Montgomery County, and points further west. Traffic and transients moved through the Palisades along the Canal, or by way of Canal and Conduit Roads, which also carried produce from the Palisades’ farms to the municipal markets and street corners throughout Georgetown and Washington. Taverns sprang along these roads and the slow-moving agricultural traffic created landmarks of its own, such as “Drover’s Rest”, a patch of cleared land between Conduit Road (the current MacArthur Boulevard) and Reservoir Road, that became the site of holding pens and livestock auctions.

The city’s major water supply main ran along Conduit Road, which was macadamized when most downtown streets were still cobblestone and outlying streets unpaved. It became a speedway for carriage racing, as well as for the “wheelmen” of the 1890s bicycling craze, and gained notoriety as a weekend speed trap long before automobiles were common.

|

|

|

The Palisades also attracted wealthier Washingtonians who built summer and week-end cottages to enjoy cool country air. To entertain late nineteenth century tourists, a hotel and gambling casino opened on the grounds of the Dalecarlia Reservoir.

In 1893, the Washington-Great Falls Electric Railroad connected the new Glen Echo Chautauqua Resort at the Maryland end of Conduit Road to the city and made the Palisades less than a 30 minute trip from the Treasury Department. Almost immediately the Palisades began to change into a suburb within the city limits.

Development in the Palisades followed the typical streetcar suburb pattern of continuous corridors, unlike the railroad suburb pattern of nodes around stations. Because streetcars made numerous stops at short intervals, developers platted rectilinear subdivisions on small lots.

Sherier Place, which runs roughly parallel to Conduit Road on the north and Canal Road on the south, closely followed the electric railway track bed. As the tracks ran north from Georgetown, they passed immediately behind the Baltimore house and other lots on the south side of Sherier Place. Near Galena Place, the tracks shifted to a center median.

|

|

In 1915, Sherier Place had just three houses. But by 1920 it had 37 houses and, by 1925, 70. This period of development paralleled the peak of kit house building in Washington, DC.

Although kit houses were sold by companies including Aladdin, Lewis, Sterling, Gordon-Van Tine, and Montgomery Ward, Sears Roebuck is generally credited with manufacturing the largest number. The company had an advantage over the others, because in 1908 when Sears issued its 44-page first Modern Homes Catalog, one out of every four Americans was already looking through a Sears general merchandise catalog.

By 1918, the Modern Homes catalog had expanded to 146 pages and included models as simple as two room cottages priced at less than $1,000 as well as the mansion-like $5,972 Magnolia. Styles included bungalows, four-squares, cottages, and colonials in wood, brick, or concrete block. But Sears did not stop at making ordering a home as easy as ordering an automobile, radio, or armoire. In 1919, Sears established a Modern Homes Sales Office in Akron, Ohio. By the end of the 1920s, there were 48 Modern Homes Sales Offices.

The Sears Roebuck house era in Washington, DC really began on April 10, 1922. On that day, Sears opened a Modern Homes sales office at 704 Tenth Street NW, which included an actual small modern house within the showroom.

|

ABOVE: From atop the Palisades, the C&O Canal is filled with stagnant olive drab water, while the Potomac lies invisible between the boughs on the DC bank and the smoggy blue-green cliffs of the Viginia shore.

BELOW: Late on a 1920s afternoon, a Glen Echo-bound trolley drops a passenger behind Sherier Place NW. "Trolley stops" on the outlying lines were simply concrete pads with wooden rail benches. Parking was free.

(Photo courtesy of Lee Rogers)

|

|

|

|

The Washington Post opined that the most interesting exhibit showed Honor-Bilt construction methods, noting that Sears also offered a liberal easy payment plan, money to help finance the building, and mortgages payable in small monthly installments. However, Sears houses had special appeal to middle and working class buyers for many of the reasons outlined in the Post article.

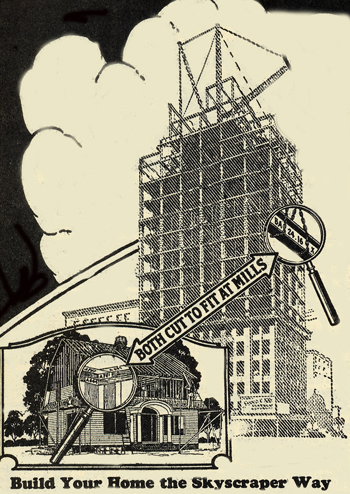

First, Sears' national buying power and distribution gave purchasers access to top quality materials not necessarily available from local suppliers. As Sears literature boasted, "we buy raw lumber direct from the best timber tracts in America" and "our mills are located right in the heart of the yellow pine districts".

|

|

|

Second, a Sears precut house promised considerable savings in architect fees, material expense, and labor cost. Sears expert Rosemary Thornton has shown that a typical architect’s 5% commission could easily represent six months of a working man’s income. In a well-publicized competition, the company claimed that a precut Rodessa bungalow could be erected in 352 carpenter hours, as opposed to 583 carpenter hours using traditional construction methods and on-site lumber cutting.

Construction costs could be further reduced by an infusion of the owner’s labor, as a Sears house could be erected by anyone with basic construction skills. As Robert Schweitzer and Michael W. R. Davis have written, Sears houses filled a niche because

“Many … people already had the land and the craft skills to erect houses, but they lacked the efficiency of lumberyard power tools for cutting and boring, and they also were at the mercy of local lumber dealers or local sawmill prices."

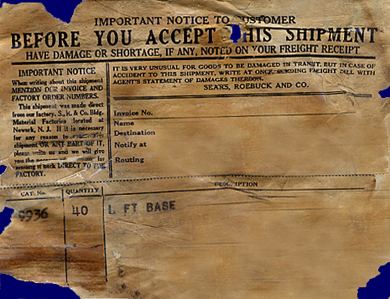

The company provided a detailed 75-page instruction manual, a full set of plans and blueprints, detailed lists of materials, and stamped identification numbers on most parts. Materials were shipped in highly organized and precisely-timed rail shipments, so that the only transportation a builder needed to arrange was from siding to building site.

Third, the Sears Modern Homes Catalog offered a full line of houses to suit families of different sizes and means. Sears offered houses in two grades of framing--Honor-Bilt and the cheaper Standard-Bilt, which had more widely-spaced joists and lighter framing.

Fourth, Sears offered vastly more liberal financing terms than most lenders of the day. At a time when standard mortgages were subject to renegotiation every three to five years and down payments were typically at least 50% of purchase price, Sears offered 15 year fixed-rate loans at up to 75% of value. The value of the lot could be applied to the down payment, as could the value of the owner’s construction labor.

The economies offered by kit house construction and a lot close to the streetcar made it possible for working class families to have homes in semi- suburban neighborhoods like the Palisades. From the opening of the Sears sales office on April 10, 1922 through mid-1928, almost 10% of the 242 of building permits issued for dwellings in the Palisades listed "Sears Roebuck" as the architect. This total probably underestimates the actual number of Sears houses in the Palisades, as some permits which did not identify an architect were probably for Sears houses. In addition, the total does not include permits issued in 1929, the Modern Homes Division’s greatest year, with sales of more than $12,000,000.

Today many Sears houses still stand in the Palisades, although most have been heavily altered as the neighborhood has grown more affluent.

|

ABOVE: While Sears' architectural styles were conservative, it promoted its technology as high tech and ultra-modern.

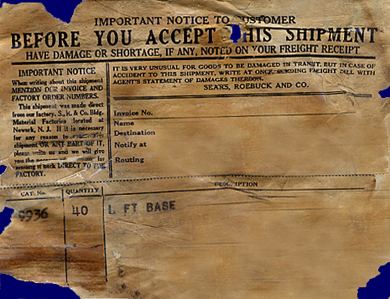

BELOW: Sears house restorers often find shipping labels glued in places like the reverse side of interior trim.

|

| |

BELOW: Today the trolley trackbed behind Sherier Place resembles a country lane. |

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE ABOUT JESSE BALTIMORE'S SEARS "FULLERTON".

CLICK HERE TO RETURN TO "SAVE THE JESSE BALTIMORE HOUSE" .

CLICK HERE FOR "HOW TO SAVE A BUILDING".

CLICK HERE TO RETURN TO THE "VICTORIAN SECRETS" HOMEPAGE. |

|

|

|